Check out this link.

http://www.ansc.purdue.edu/SP/MG/Documents/copper_wire.pdf

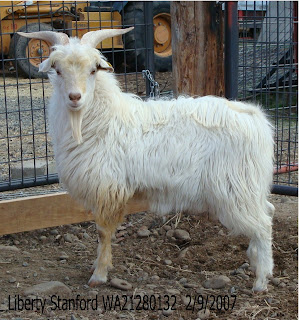

AMERICAN CASHMERE GOATS

28.11.11

25.8.11

EAR TAGS

PREMIER 1 SUPPLY

How ear tags can help you…

1. Can indicate sex

Benefit?

Allows rapid sorting by sex while sheep and goats are moving down a chute or in a holding pen. No need to get your hands dirty or spend expensive time to check “the plumbing.”

How to do this:

• Males: Insert primary tag in left ear

• Females: Insert primary tag in right ear

2. Can indicate year of birth

Benefit?

No need to catch them to check their teeth. A tag will tell you the age from 40 ft away. Enables faster

decisions when sorting for culling or breeding.

Two ways to do this:

a. Use a different color for each year. Lambs with purple tags were born in 2007. Lamb with yellow tag 2006.

b. Begin tag number series with the year of birth. Tag 7275 indicates lamb is the 275th lamb tagged in 2007.

3. Can indicate sire (& dam)

Benefit?

No need to check records for breeding decisions.

Three ways to do this:

a. Use a different-color second tag for each sire

(blue tags = Sire XYZ; purple tags = Sire ABC).

b. Have sire name printed on the tag of its progeny.

(We will do this for you at no extra cost.)

c. Hand-write the ewe’s tag number with a marking pen on the lamb’s tag. If space is limited write it on the inner surfaces of the tag.

Note: Since tags can be lost, we strongly advise using 2 sire/dam tags (one in each ear).

4. Can indicate single, twin or triplet

Benefit?

Speeds up sorting for breeding and sale purposes. Reduces need to keep and consult records.

To do this: Use a different color for each. Repeat this color year after year.

At Premier—

• blue = single

• green = twin

• orange = triplet

5. Can indicate problems

Benefit?

Allows rapid, positive culling for animals with foot problems, dystocia, mastitis, prolapse, etc.

Two ways to do this:

a. Snap a black tag in every problem animal.

b. Use an ear notcher to mark the animal.

Ear Tag FAQ

How can I reduce tag losses?

• Insert tag midway between the skull and the tip of the ear (see diagram below). We observed in our own sheep over the years that tags placed very close to the skull in sheep were more likely to become infected.

Why? A combination of the tissue being thicker and the wound less able to heal (not enough air to dry it up).

• Avoid the large veins in the ear

Why? When damaged, the veins heal slowly and are more prone to infection.

• Don’t use nylon (e.g. Snapp or Swivel) tags as long-term tags.

Why? UV light will eventually cause them to become brittle.

• Avoid double-button round tags for sheep and goats.

Why? They are more likely to snag and tear on grass and wire fences.

• Avoid low-fiber diets.

Why? Sheep on high-grain or liquid diets are desperate to chew. If one starts chewing tags, its penmates will soon do likewise and pull the tags out. For maximum retention and the lowest risk of bleeding and infection, place ear tags in either of the 2 red spots. (One-piece loop tags only fit in the lower red spot.) Avoid the large veins.

How do I keep track of an animal if a tag falls out?

1. Install 2 tags (one in each ear)—with the same number. Official tags can’t be duplicated—but you can use the same individual animal number on the second “backup” tag if you don’t add a flock or premise number.

2. Tattoo the animal. No animal number is more permanent.

What tags does Premier use?

We are always experimenting, so we use many tags. Our preferred system is to:

1. Tag baby lambs with 2 EasyTags, size 1 (same numbers for each tag) within 4 weeks of lambing.

2. Use tag color/numbers/placement to indicate twin-single-triplet/year of birth/sex.

3. For lambs we retain, we substitute an EasyTag, size 5 tag (much easier to see at distance) in the same hole.

4. Never install official tags until the animal is ready to leave the farm. Why our applicator design is

different from others…Good tag retention requires accurate placement (between the veins, midway

between skull and tip of ear, etc.). Tagging sheep and goat ears requires more care and precision than cattle ears because their ears are small. Accurate placement is difficult if the tag projects forward from the applicator (as it does for most applicators)—because a sheep/goat

will jerk its head away as soon as a tag touches an ear.

That’s why Premier’s tag applicator holds the flag portions of the tag back inside the applicator— away from the ear. That means animals won’t feel anything until you squeeze it shut.

How long does it take to get ear tags from Premier?

Less than 2 business days to print and ship them. Then it’s up to UPS ground or US mail to get it to you. We can expedite the shipment—but it will cost you more for the faster shipping methods.

Custom-imprinted tags?

• We will custom imprint tags with your choice of numbers, farm/ranch name, brands and/or logos.

Consecutive numbers and farm/ ranch names are free! Brands or logos have a one-time $15 setup fee.

• Can we imprint numbers out of sequence or individual names? Yes. But it takes more time per tag so the cost is $1.50 per tag (for any tag size).

What tag colors imprint the best—and the worst?

The tag colors in the charts on pp. 14–17 are arranged in order of readability from a distance.

Light colors such as spearmint, salmon, yellow and white tags are the most readable from a distance.

Dark colors such as brown, purple and red are the least readable.

Premier Tip…

If you use tags in your breeding flock, it’s wise to install a tag in both ears when they are baby lambs.

Why? Because lamb wounds heal quickly. And it’s easy to cut out the first tag and install a larger tag without stess to the animal or risk of infection.

13.12.10

Minerals

Fias Co Farm

Molly Nolte

4659 Seneca Drive

Okemos, MI 48864

We offer loose minerals, free choice, at all times. We offer it in a way that it cannot be "soiled" (stepped in or pooped in), because if it does get soiled, the goat will not eat it. We do not use mineral blocks because the kids climb on them and soil them and then the goats will not use it.

We use a cattle mineral mix that we can find, and buy, locally and has in it what we want for our goats. We mix it equal parts minerals to Diamond V Yeast Culture.

Diamond V Yeast Culture XP-DFM (which you should be able to order through your local feed store) is all natural and helps increase ruminal yeasts and bacteria, which, in turn, aids in digestion and helps the goats better utilize their food. It a sense, think of it as a "food booster". It also contains extra protein and vitamins. (NOTE: This is not the same thing as brewers yeast, bread yeast or nutritional yeast.) We find when we feed this yeast our goats health is generally better and their coats are shinier in the summer and thicker in the winter. We also find that it increases milk yield. There are a few forms of Diamond V Yeast such as XP and XP-DFM. We use, and really like, the "XP-DFM" . This XP-DFM is on the expensive side

($40 per 50 lb. bag), and we have to have our local feed store special order it for us, but it lasts a very long time and we feel it is most definitely worth the cost and effort. Just ask your feed store to special order it.

Do not use a mineral mix labeled for "sheep and goats". This mix is really just for sheep and will not contain copper (sheep can't have copper). Goats do need copper. You are better off using a general livestock mix.

Look for mixes that contain the proper ratio of about 2 parts Calcium to 1 part Phosphorus.

We also offer baking soda free choice in a separate container. Baking soda aids the goat to buffer their rumen, which aids in digestion and helps avoid bloat. The goats will use it if they need it. If the baking soda "gets old" and you feel it is time to refresh it, just sprinkle the old remainder soda on a stall floor.

Goats like their minerals and baking soda fresh, so I offer only as much as they will finish off in a couple of days. This helps avoid waste.

We offer our minerals in such a way that the goats can't "soil" them. We hang the mineral feeders, which we have modified by cutting out a section in the middle so they will hang on a modified "livestock panel". We have modified the livestock panel by using bolt cutters to remove a section. The goats can now stick their heads through the panel to get to the minerals, but cannot step in them. The other side of the panel is our chicken coop, and the goats are not allowed in there, so they cannot get at the minerals from the other side. Hardware cloth keeps the chicken out of the minerals from the other side.

Fias Co Farm

Copyright (c) 1997-2010

Molly Nolte. All rights reserved.

http://fiascofarm.com/

Molly Nolte

4659 Seneca Drive

Okemos, MI 48864

We offer loose minerals, free choice, at all times. We offer it in a way that it cannot be "soiled" (stepped in or pooped in), because if it does get soiled, the goat will not eat it. We do not use mineral blocks because the kids climb on them and soil them and then the goats will not use it.

We use a cattle mineral mix that we can find, and buy, locally and has in it what we want for our goats. We mix it equal parts minerals to Diamond V Yeast Culture.

Diamond V Yeast Culture XP-DFM (which you should be able to order through your local feed store) is all natural and helps increase ruminal yeasts and bacteria, which, in turn, aids in digestion and helps the goats better utilize their food. It a sense, think of it as a "food booster". It also contains extra protein and vitamins. (NOTE: This is not the same thing as brewers yeast, bread yeast or nutritional yeast.) We find when we feed this yeast our goats health is generally better and their coats are shinier in the summer and thicker in the winter. We also find that it increases milk yield. There are a few forms of Diamond V Yeast such as XP and XP-DFM. We use, and really like, the "XP-DFM" . This XP-DFM is on the expensive side

($40 per 50 lb. bag), and we have to have our local feed store special order it for us, but it lasts a very long time and we feel it is most definitely worth the cost and effort. Just ask your feed store to special order it.

Do not use a mineral mix labeled for "sheep and goats". This mix is really just for sheep and will not contain copper (sheep can't have copper). Goats do need copper. You are better off using a general livestock mix.

Look for mixes that contain the proper ratio of about 2 parts Calcium to 1 part Phosphorus.

We also offer baking soda free choice in a separate container. Baking soda aids the goat to buffer their rumen, which aids in digestion and helps avoid bloat. The goats will use it if they need it. If the baking soda "gets old" and you feel it is time to refresh it, just sprinkle the old remainder soda on a stall floor.

Goats like their minerals and baking soda fresh, so I offer only as much as they will finish off in a couple of days. This helps avoid waste.

We offer our minerals in such a way that the goats can't "soil" them. We hang the mineral feeders, which we have modified by cutting out a section in the middle so they will hang on a modified "livestock panel". We have modified the livestock panel by using bolt cutters to remove a section. The goats can now stick their heads through the panel to get to the minerals, but cannot step in them. The other side of the panel is our chicken coop, and the goats are not allowed in there, so they cannot get at the minerals from the other side. Hardware cloth keeps the chicken out of the minerals from the other side.

Fias Co Farm

Copyright (c) 1997-2010

Molly Nolte. All rights reserved.

http://fiascofarm.com/

VITAMIN AND MINERAL DEFICIENCIES IN GOATS

Suzanne W. Gasparotto

HC 70 Box 70

Lohn, TX 76852

Phone 325/344-5775

Originators of Tennessee Meat Goats

VITAMIN AND MINERAL DEFICIENCIES IN GOATS

Proper vitamin and mineral levels are essential to the good health of goats. Although no single mineral can be singled out as more important than others, copper, zinc, and selenium levels are especially critical. The interaction of minerals is astoundingly complex. The most difficult task in raising goats is getting nutrition right, and vitamins and minerals are key. Most producers are not knowledgeable enough to formulate their own feed ration with appropriate levels of minerals and vitamins included. Achieving this is a complex task that is best left to a trained goat nutritionist.

Selenium: Major portions of the United States have soils that are deficient in selenium. Selenium deficiency is widespread in most of the eastern coast of the U.S., into the Great Lakes area, and throughout the northwestern part of this country. Plants grown in these soils are selenium deficient and therefore cannot provide adequate selenium to the goats that eat them.

Selenium deficiency, like Vitamin E deficiency, can cause white muscle disease (nutritional muscular dystrophy), causing the goat to have difficulty controlling its muscles. Newborns with weak rear legs may be selenium-deficient. Kids may be too weak to nurse their dams. Pneumonia may result from weakness in muscles that control breathing.

Producers raising goats in areas having selenium-deficient soil must make sure that this mineral is added to feed. Many producers give BoSe injections to newborn kids, as well as to adult goats. BoSe is a vet prescription item. Contact the local county extension agent or your veterinarian for information on your particular area or google 'selenium levels United States' for data.

Zinc: Zinc is needed in the synthesis of proteins and DNA and in cell division. Excessive salivation, deformed hooves, stiff joints, chronic skin problems, abnormally small testicles, and reduced interest in mating are some of the signs.

Copper and Molybdenum: Unlike sheep, for whom copper is toxic, goats must have copper in their diet. Inadequate copper levels can cause loss of hair color, coarse hair that has hooked end tips, abortions, stillbirths, anemia, frequent bone fractures, poor appetite, weight loss, and decreased milk production.

Molybdenum and copper amounts must be balanced or health problems appear. More than 3 ppm of molybdenum binds up copper and creates a deficiency of copper in the goat.

It is also possible to cause copper toxicity in goats by feeding too much copper. Researchers and producer experiences seem to be proving that goats need more copper than originally believed. Make sure that the copper level in feed is correct for your goats by consulting a trained caprine nutritionist knowledgeable about your area.

Water: Yes, water. The goat's body is normally more than 60% water. Rumen contents must be about 70% water to function properly. Even a slight dip in water consumption can result in a goat with fever and off feed.

Iron: Unless a goat is anemic, iron deficiency is generally not a problem in foraging goats. Certain onion-type plants can, however, cause anemia. Stomach worms, sucking lice, and blood loss are common causes of anemia in goats. Goats that are seriously ill with anemia may be supplemented with injectable iron (Ferrodex 100) or oral adminstration of Red Cell. Conversely, an excess of iron can contribute to decreased fertility in goats.

Iodine: Iodine is as essential in goats' diets as it is in humans. Goiters are the most visible sign of iodine deficiency. Newborns whose dams are iodine deficient can be born with goiters. Commercial feeds and minerals contain non-iodized salt, so it may be necessary to offer iodized salt on a free-choice basis. A quicker method of getting iodine into the goat is to paint 7% iodine on the hairless tailweb and to offer kelp (seaweed) free choice.

Calcium and Phosphorus: Calcium and phosphorus must be in proper balance or serious illnesses can occur. Female goats that have been bred at too young of an age can develop lameness and/or bowed legs if they are calcium deficient. Calcium is essential to bone formation and muscle contractions (including labor contractions). A calcium-to-phosphorus ratio of 2-1/2 to 1 is proper and helps prevent urinary calculi. Too much phosphorus in relation to calcium causes urinary calculi. An imbalance of calcium and phosphorus can result in birth defects.

Salt: If a goat lacks salt in its diet, it may be seen licking the ground -- trying to get salt from the dirt. Offer salt as part of an appropriate mineral mix on a free-choice basis. Do not force-feed salt by mixing it with processed feed; this procedure is used to limit feed consumption. Salt is often used as a feed limiter, as heavily salted rations cause goats to eat less. A pregnant doe who consumes too much salt may have udder problems -- edema (subcutaneous accumulation of fluids).

Sulfur: Excessive salivation may be a sign of sulfur deficiency. A properly balanced loose mineral and vitamin mix is required. Direct supplementation of sulfur can result in the binding up of iron and copper.

Potassium: Goats on forage usually get all the potassium they need. Penned animals need potassium added to their processed grain mix. Emaciation and muscle weakness are signs of severe potassium deficiency.

Magnesium: Goats deficient in magnesium have lowered urine and milk production and may become anorexic.

Manganese: Slow growth rates in kids (especially buck kids), reduced fertility and abortions in does, improperly formed legs, and difficulty in walking are general signs of manganese deficiency. Too much calcium interferes with manganese absorption.

Vitamin A: Inadequate amounts of Vitamin A in a goat's diet can lead to thick nasal discharge, difficulty in seeing or blindness, respiratory diseases, susceptibility to parasites, scruffy hair coat, and diarrhea. Kids with coccidiosis need more Vitamin A because they have reduced intestinal absorption of nutrients. Adults are likely to be less fertile and more susceptible to diseases if they do not have adequate levels of this essential fat-soluble vitamin.

B Vitamins: A sick goat must be supplemented with B vitamins, particularly Vitamin B 1 (thiamine). The B vitamins are water soluble, so they need to be replenished daily. One of many conditions that depletes the goat's body of B vitamins is diarrhea (which is a symptom of greater problems). Goats whose rumens are not functioning properly or have had their feed regimen changed should be supplemented with B vitamins, particularly B1 (thiamine).

One of the most common examples of Vitamin B1 (thiamine) deficiency is polioencephalomalacia (goat polio). Thiamine must be given to counteract severe neurological problems. Thiamine-deficient goats display rigid bent necks that won't straighten and a loss of eye focus. This disease usually results from eating moldy hay, feed, or sileage; however, it occasionally occurs because the organism exists under certain environmental conditions and a susceptible goat picks it up. The symptoms mimic those of tetanus and dehydration. Because all B vitamins are water soluble, it is difficult to overdose them.

Vitamin B12, an injectable red liquid requiring a vet prescription, is essential in the treatment of anemia.

Vitamin D: Enlarged joints and bowed legs (rickets) are a result of Vitamin D deficiency. Penned goats must have Vitamin D added to their feed.

Vitamin E: Feeding sileage or old hay can produce Vitamin E deficiency and result in white muscle disease. The injectable prescription product BoSe contains both selenium and vitamin E and is often given to newborns in selenium-deficient areas. Vitamin A-D-E Gel is available for supplemental oral use.

Conclusion

This list is by no means comprehensive but is intended to provide a producer overview. If you get nothing else from this article, understand that proper goat nutrition is very complex and not for amateurs.

For producers affected by Tall Fescue Toxicity, several companies around the USA make a fescue-balancer loose mineral. If mineral deficiencies are widespread in your herd, Mineral Max II is available. An injectable cobalt-blue colored liquid that must be obtained from a vet, Mineral Max II contains zinc, manganese, selenium, and copper in chelated (timed-release) form. It is given to goats IM (into the muscle) usually one injection per year and in decreasing amounts as the goat ages. Mineral Max II is made by Sparhawk Labs in Lenexa, Kansas for RXV Products in Westlake, Texas. It may be available under other brand names. Do not give BoSe and Mineral Max II together.

Producers who live near a feed mill that makes commercial goat feed are encouraged to use their services and purchase their products. Such firms employ livestock nutritionists who have knowledge of the nutritional needs of goats in the areas for which they manufacture their products. If such mills are non-existent in your area, contact your county extension agent or closest agricultural university for assistance. These folks should have knowledge about feed mixtures that the average producer does not possess. Find out what your area is deficient in and make sure that is added into your feed supply.

Do not attempt to formulate your own feed unless you are a trained goat nutritionist. If such expertise is not available in your area, locate and hire a goat nutritionist to formulate a feed ration for you. This service is not expensive but you may be required to buy four to six tons of feed, so contact your neighboring goat producers about working together on this purchase. There are computer programs into which the nutritionist can input information unique to your farm and your management techniques to develop a feed mix specifically for your needs. The health and well-being of your goats are depending upon your making wise decisions about their nutrition. Find a place to cut costs other than goat nutrition. You cannot starve a profit out of a goat.

Suzanne W. Gasparotto

ONION CREEK RANCH

5-11-09

HC 70 Box 70

Lohn, TX 76852

Phone 325/344-5775

Originators of Tennessee Meat Goats

VITAMIN AND MINERAL DEFICIENCIES IN GOATS

Proper vitamin and mineral levels are essential to the good health of goats. Although no single mineral can be singled out as more important than others, copper, zinc, and selenium levels are especially critical. The interaction of minerals is astoundingly complex. The most difficult task in raising goats is getting nutrition right, and vitamins and minerals are key. Most producers are not knowledgeable enough to formulate their own feed ration with appropriate levels of minerals and vitamins included. Achieving this is a complex task that is best left to a trained goat nutritionist.

Selenium: Major portions of the United States have soils that are deficient in selenium. Selenium deficiency is widespread in most of the eastern coast of the U.S., into the Great Lakes area, and throughout the northwestern part of this country. Plants grown in these soils are selenium deficient and therefore cannot provide adequate selenium to the goats that eat them.

Selenium deficiency, like Vitamin E deficiency, can cause white muscle disease (nutritional muscular dystrophy), causing the goat to have difficulty controlling its muscles. Newborns with weak rear legs may be selenium-deficient. Kids may be too weak to nurse their dams. Pneumonia may result from weakness in muscles that control breathing.

Producers raising goats in areas having selenium-deficient soil must make sure that this mineral is added to feed. Many producers give BoSe injections to newborn kids, as well as to adult goats. BoSe is a vet prescription item. Contact the local county extension agent or your veterinarian for information on your particular area or google 'selenium levels United States' for data.

Zinc: Zinc is needed in the synthesis of proteins and DNA and in cell division. Excessive salivation, deformed hooves, stiff joints, chronic skin problems, abnormally small testicles, and reduced interest in mating are some of the signs.

Copper and Molybdenum: Unlike sheep, for whom copper is toxic, goats must have copper in their diet. Inadequate copper levels can cause loss of hair color, coarse hair that has hooked end tips, abortions, stillbirths, anemia, frequent bone fractures, poor appetite, weight loss, and decreased milk production.

Molybdenum and copper amounts must be balanced or health problems appear. More than 3 ppm of molybdenum binds up copper and creates a deficiency of copper in the goat.

It is also possible to cause copper toxicity in goats by feeding too much copper. Researchers and producer experiences seem to be proving that goats need more copper than originally believed. Make sure that the copper level in feed is correct for your goats by consulting a trained caprine nutritionist knowledgeable about your area.

Water: Yes, water. The goat's body is normally more than 60% water. Rumen contents must be about 70% water to function properly. Even a slight dip in water consumption can result in a goat with fever and off feed.

Iron: Unless a goat is anemic, iron deficiency is generally not a problem in foraging goats. Certain onion-type plants can, however, cause anemia. Stomach worms, sucking lice, and blood loss are common causes of anemia in goats. Goats that are seriously ill with anemia may be supplemented with injectable iron (Ferrodex 100) or oral adminstration of Red Cell. Conversely, an excess of iron can contribute to decreased fertility in goats.

Iodine: Iodine is as essential in goats' diets as it is in humans. Goiters are the most visible sign of iodine deficiency. Newborns whose dams are iodine deficient can be born with goiters. Commercial feeds and minerals contain non-iodized salt, so it may be necessary to offer iodized salt on a free-choice basis. A quicker method of getting iodine into the goat is to paint 7% iodine on the hairless tailweb and to offer kelp (seaweed) free choice.

Calcium and Phosphorus: Calcium and phosphorus must be in proper balance or serious illnesses can occur. Female goats that have been bred at too young of an age can develop lameness and/or bowed legs if they are calcium deficient. Calcium is essential to bone formation and muscle contractions (including labor contractions). A calcium-to-phosphorus ratio of 2-1/2 to 1 is proper and helps prevent urinary calculi. Too much phosphorus in relation to calcium causes urinary calculi. An imbalance of calcium and phosphorus can result in birth defects.

Salt: If a goat lacks salt in its diet, it may be seen licking the ground -- trying to get salt from the dirt. Offer salt as part of an appropriate mineral mix on a free-choice basis. Do not force-feed salt by mixing it with processed feed; this procedure is used to limit feed consumption. Salt is often used as a feed limiter, as heavily salted rations cause goats to eat less. A pregnant doe who consumes too much salt may have udder problems -- edema (subcutaneous accumulation of fluids).

Sulfur: Excessive salivation may be a sign of sulfur deficiency. A properly balanced loose mineral and vitamin mix is required. Direct supplementation of sulfur can result in the binding up of iron and copper.

Potassium: Goats on forage usually get all the potassium they need. Penned animals need potassium added to their processed grain mix. Emaciation and muscle weakness are signs of severe potassium deficiency.

Magnesium: Goats deficient in magnesium have lowered urine and milk production and may become anorexic.

Manganese: Slow growth rates in kids (especially buck kids), reduced fertility and abortions in does, improperly formed legs, and difficulty in walking are general signs of manganese deficiency. Too much calcium interferes with manganese absorption.

Vitamin A: Inadequate amounts of Vitamin A in a goat's diet can lead to thick nasal discharge, difficulty in seeing or blindness, respiratory diseases, susceptibility to parasites, scruffy hair coat, and diarrhea. Kids with coccidiosis need more Vitamin A because they have reduced intestinal absorption of nutrients. Adults are likely to be less fertile and more susceptible to diseases if they do not have adequate levels of this essential fat-soluble vitamin.

B Vitamins: A sick goat must be supplemented with B vitamins, particularly Vitamin B 1 (thiamine). The B vitamins are water soluble, so they need to be replenished daily. One of many conditions that depletes the goat's body of B vitamins is diarrhea (which is a symptom of greater problems). Goats whose rumens are not functioning properly or have had their feed regimen changed should be supplemented with B vitamins, particularly B1 (thiamine).

One of the most common examples of Vitamin B1 (thiamine) deficiency is polioencephalomalacia (goat polio). Thiamine must be given to counteract severe neurological problems. Thiamine-deficient goats display rigid bent necks that won't straighten and a loss of eye focus. This disease usually results from eating moldy hay, feed, or sileage; however, it occasionally occurs because the organism exists under certain environmental conditions and a susceptible goat picks it up. The symptoms mimic those of tetanus and dehydration. Because all B vitamins are water soluble, it is difficult to overdose them.

Vitamin B12, an injectable red liquid requiring a vet prescription, is essential in the treatment of anemia.

Vitamin D: Enlarged joints and bowed legs (rickets) are a result of Vitamin D deficiency. Penned goats must have Vitamin D added to their feed.

Vitamin E: Feeding sileage or old hay can produce Vitamin E deficiency and result in white muscle disease. The injectable prescription product BoSe contains both selenium and vitamin E and is often given to newborns in selenium-deficient areas. Vitamin A-D-E Gel is available for supplemental oral use.

Conclusion

This list is by no means comprehensive but is intended to provide a producer overview. If you get nothing else from this article, understand that proper goat nutrition is very complex and not for amateurs.

For producers affected by Tall Fescue Toxicity, several companies around the USA make a fescue-balancer loose mineral. If mineral deficiencies are widespread in your herd, Mineral Max II is available. An injectable cobalt-blue colored liquid that must be obtained from a vet, Mineral Max II contains zinc, manganese, selenium, and copper in chelated (timed-release) form. It is given to goats IM (into the muscle) usually one injection per year and in decreasing amounts as the goat ages. Mineral Max II is made by Sparhawk Labs in Lenexa, Kansas for RXV Products in Westlake, Texas. It may be available under other brand names. Do not give BoSe and Mineral Max II together.

Producers who live near a feed mill that makes commercial goat feed are encouraged to use their services and purchase their products. Such firms employ livestock nutritionists who have knowledge of the nutritional needs of goats in the areas for which they manufacture their products. If such mills are non-existent in your area, contact your county extension agent or closest agricultural university for assistance. These folks should have knowledge about feed mixtures that the average producer does not possess. Find out what your area is deficient in and make sure that is added into your feed supply.

Do not attempt to formulate your own feed unless you are a trained goat nutritionist. If such expertise is not available in your area, locate and hire a goat nutritionist to formulate a feed ration for you. This service is not expensive but you may be required to buy four to six tons of feed, so contact your neighboring goat producers about working together on this purchase. There are computer programs into which the nutritionist can input information unique to your farm and your management techniques to develop a feed mix specifically for your needs. The health and well-being of your goats are depending upon your making wise decisions about their nutrition. Find a place to cut costs other than goat nutrition. You cannot starve a profit out of a goat.

Suzanne W. Gasparotto

ONION CREEK RANCH

5-11-09

22.4.10

Prevention of Diseases

Suzanne W. Gasparotto

Lohn, TX 76852

Phone 325-344-5775

Originator of Tennessee Meat Goats

DISEASES OF GOATS: PREVENTION, CONTROL, AND MANAGEMENT

A major concern of responsible goat producers is the introduction of diseases onto their property. Prevention is of course the producer's desire, but realistically speaking, control and management are most likely to be goal.

Disease can enter the producer's farm or ranch from many sources. Introducing new animals is the usual avenue but definitely not the only way that illness finds its way into the herd.

1) Bringing new animals into the herd from offsite. Quarantine and handling procedures will be addressed in this article.

2) Offering stud service. This typically involves bringing other producers' does onto the property for service by an on-site buck.

3) Goat shows. A huge source of infection and illness, shows are like children's day-care centers -- incubators for disease.

4) Visitors. Infectious materials can enter on visitors' shoes, clothing, and hair; on the tires of their vehicles; in hay, water, tubs/buckets, feed and other supplies that visitors have brought with them.

5) Unclean conditions in pens and pastures.

6) Poor health management practices within the herd.

7) The producer's family members and pets.

Most producers are aware that they should quarantine new animals brought from outside the ranch property in order to protect their goats from whatever diseases the new animals might be carrying. However, the reverse is just as true: newly-introduced goats need to be protected from organisms present on the ranch to which they've never had their immune systems previously exposed. Recognize that these goats are on a new property in a changed environment and often in a much different climate from which they had been previously adapted for living. From the moment they left their previous homes, these new goats' immune systems are under constant assault.

Set up a pen and shelter sized to accommodate the producer's anticipated needs and locate it away from pens and pastures where healthy animals are regularly kept. The pen should be large enough to provide space for proper exercise and should have at least a three-sided shelter with roof to protect the new goats from bad weather. Nearby but not within this pen/shelter area, there should be several smaller gated pens and sheds where sick and/or contagious animals can be confined for observation and treatment. Place a shallow plastic cat-litter pan and a gallon of bleach outside each pen and require persons entering and exiting to wet the soles of their shoes in the bleach. The producer and all other persons handling these goats should consider using disposable gloves.

New and/or ill goats should be kept in appropriate parts of these "sick pens." Goats new to the ranch should be quarantined for a minimum of four weeks, during which time they should be dewormed, vaccinated, and otherwise examined, based upon the producer's management practices. If blood testing for specific diseases is part of the program, do it while the goats are in quarantine. If the tests come back positive and the new goats are already running with the main herd, exposure to disease has probably already occurred.

Offering breeding services on the ranch is an avenue for contamination. Before making a decision to offer such services, the producer should read this writer's Article entitled Pros and Cons of Offering Breeding Services on the Articles page at www.tennesseemeatgoats.com. A lot of decisions must be made and agreements put into writing before the first goat arrives on the servicing ranch.

Participating in goat shows is almost a no-win situation with regard to disease. The producer must take extraordinary precautions to protect both goats and human participants from exposure to contagious bacteria, viruses, and other organisms. Animals and people, both young and adult, present risks to all in attendance. Consult an experienced goat-show participant to find out what steps to take to protect you and your goats from taking "unwanted visitors" home with you. At the very minimum, sick goats and ill people should not attend shows and should not be allowed to participate. If they are, leave immediately. Don't even unload your animals. The health of your goats is much more important than a forfeited entry fee or a winning ribbon.

Visitors, relatives, children, pets, and even the producer can easily bring to the ranch infectious bacteria, viruses, and other organisms without ever realizing it. Using a shallow plastic cat-litter pan and a bottle of bleach, the producer should have all visitors step through the solution. This is the very minimum protective action that goat ranchers should take. If the producer knows that visitors or family members have had direct access to goats from outside the ranch, then those folks should be asked to change clothes and shoes before they enter your property. A visit by kids to the 4H barn is a good source of contamination -- a fact that probably never crosses peoples' minds.

Unclean/unsanitary pens, feed troughs, and water containers are excellent sources of infection -- worms and coccidia oocysts thrive in these environments. Flies carry disease from goat to goat. Less often recognized is the exposure to disease that occurs when infective birthing materials are left in pens/pastures for healthy goats to contact. Infected placentas left lying around after birthing are transmitters of abortion diseases such as chlamydiosis; many other diseases are spread through placental material and mucous secretions. Footrot/footscald is highly infectious and contaminated ground very efficiently spreads these diseases. Viral-borne diseases such as some types of Pinkeye at quickly passed around in crowded herds. Caprine Arthritic Encelphalitis (CAE) is a viral disease that is spread through body fluids and mother's milk. Cutting open and draining an active Caseous Lymphadinitis (CL) abscess and exposing the exudate (pus) to other goats and the ground upon which they walk is one of the main ways that CL is spread throughout a herd. Reusing contaminated needles, syringes, and scalpels is another easy way to transmit disease.

Raising quality goats requires planning and hard work. Doing the planning part in advance will cut down on the amount of hard work each producer faces daily.

How to select a healthy goat

by Patricia Stewart

Picking a healthy goat is very important whenever you are bringing a new goat home. There are some nasty diseases with no cures, and once they get established in your soil, there's nothing you can do but start over on a new piece of land. Start out by just observing behavior and general coat condition. A healthy goat should have clear eyes and nose, a shiny hair coat with no bald patches, and a twinkle in its eye. Bald patches may be a sign of a mite or lice infection, causing the goat to rub due to irritation.

If you are buying from a breeder, ask them if they test for CAE, Caprine Arthritic Encephalitis. This disease has been an issue for a long time in goats, and thankfully, conscientious goat farmers are finally taking it seriously. There are three blood tests, any of which will give you a heads up if there's a problem. Any possibly "positive," should be automatically checked with one of the other tests to verify. CAE shows up after awhile with stiff and swollen legs, awkward walking, sometimes a click from the knees of an infected goat. The udder is often hard and the animal's coat may be oily or scaly. If you are buying from a large farm, ask if they practice CAE prevention, which means the kids are bottle fed, never nursing off of mom. CAE is most commonly spread in the milk, but often doesn't show up as an illness for many months or years.

If you see any signs of swelling beneath the jaw or any oozing sores, do not buy that goat. Do not buy a goat from that farm, and wash your hands immediately. Caseous lymphadentitis, CL, is a highly contagious disease spread by discharge. The abcesses swell up in the lymph glands and as they pop, they spread the disease.

Always ask the seller what type of vaccinations they give. When was the last time the goat was wormed, and what kind of wormer was used. A healthy goat should not have visible ribs or backbone. It should have healthy pink eyelids and gums and manure that comes in pellets, individually. A goat that is passing runny or clumpy manure is not at its best. It may just be a rich diet or stress, or it may have a severe case of worms.

Keeping a goat healthy is really pretty easy. Good hay, adequate grain, fresh water and draft free home. But curing a sick goat is often impossible. I would not recommend ever buying from a sale barn, as those animals are exposed to many different germs under high stress conditions. This makes the more susceptible to bringing a problem home with them. Often times, the animals are taken to the sale barn because they are sick, or old, and the owner can't, or doesn't want to invest in healing them.

It's a good idea to keep any new goat in isolation from the existing herd, for at least two weeks. Usually, if something is "brewing" that is enough time to see how the animal does, without endangering the rest of the herd. But remember, goats are herd animals, so if possible, buy two new ones, at least, so they can keep each other company during the quarantine. They'll be much hardier and happier that way.

Introduction to a Meat Goat Quality Assurance Program

and HACCP Roger Merkel

Langston University

Biosecurity PPP #1 - Establish a biosecurity plan for your farm

Consider your production operation and devise a plan to ensure your animals are protected from diseases entering your herd. Potential ways in which diseases could enter your farm include: visitors, feed deliveries, new animal acquisition, and show animals returning to the herd, stray animals, rodents, birds, and others. The potential risk from these various areas should be examined in the context of your production situation. Plans should be made to protect animals from identified risks and to deal with animals that become ill so that diseases occurring on your farm are not transmitted beyond your farm gate.

Biosecurity PPP #2 - Minimize or avoid contact between your animals and animals not on your farm

Many diseases are transmitted through animal to animal contact. Avoiding contact with animals not on your farm will reduce disease outbreaks. Consider the location of pastures and grazing areas in relation to your neighbors’ animals. If new facilities are planned, consider the location of neighboring livestock barns and pens. Do not build facilities in or near drainage areas from livestock facilities. If your animals are very valuable, for example breeding males whose semen is collected for sale; consider double fencing along adjoining property lines to further protect them from neighboring animals. At exhibitions, house animals using solid partitions to minimize contact. Control stray animals, both domestic and wild. Maintain quarantine procedures. Do not haul other animals with your own and clean mud and manure from livestock trailers.

Biosecurity PPP #3 - Establish a quarantine protocol for animals entering your herd

Preventing diseases entering your herd from new animals begins during purchase. Be sure to ask the seller for health and production records on animals you plan to buy. Ask about the disease or herd health program followed. Also, look at the whole herd, not just the few animals you plan to purchase. This will give an indication of the health program followed. Upon arrival at your farm, place new animals in quarantine for a minimum of 30 days. Consult a veterinarian for a quarantine vaccination and deworming protocol and any diagnostic tests that should be performed. Buckets, shovels, fencing, etc., used in the quarantine area should not be moved and used in the general herd. Feed and care for quarantined animals last and do not re-enter your herd before changing clothing and washing boots to prevent carrying diseases from new animals to your herd. As an example, if a quarantined animal has a caseous lymphadenitis abscess that bursts, a person may inadvertently step in the pus from that abscess and carry that on his or her boots. If that person then reenters the farm herd, he may contaminate the ground or other animals.

Quarantine animals upon return from exhibitions or fairs if they have had contact with other animals. Follow the same quarantine guidelines for these animals as with purchased animals. Do not haul animals other than your own to and from shows.

Biosecurity PPP #4 - Establish a protocol for visitors to your farm

Many visitors to your farm will likely be producers themselves. To ensure that diseases are kept from entering your farm area, establish a protocol for any visitors and their vehicles. Control traffic entering your farm and have a separate parking area or ensure that vehicles are clean of mud and manure. This includes livestock trailers, feed delivery trucks, and veterinary vehicles. Consider having disposable boots available for visitors who wish to tour your facilities and herd. Alternatively, have a footbath with disinfectant where visitors can clean their shoes before and after seeing your animals. Have a wash basin or facility for visitors to wash their hands before and after handling animals. Explain that your procedures protect not only your herd, but theirs as well.

Biosecurity PPP #5 - Do not allow persons who have had contact with livestock in foreign countries on your farm, or bring clothing or other items from them to your farm, for a period of 5 days after their arrival in the U.S.

Largely in response to outbreaks of Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) in other countries, the USDA published guidelines for persons from, or who have traveled to, foreign countries where FMD is present. These persons are encouraged not to have contact with livestock for 5 days after entering the U.S. Some states or institutions, such as Langston University, recommend a 10-day waiting period. The virus causing FMD can be carried in hair and nasal passages, clothing, luggage, shoes, etc. Following this PPP helps safeguard the entire U.S. livestock industry. Outbreaks of FMD, while not a threat to humans, result in the necessary destruction of all infected and potentially infected animals with enormous industry and economic consequences.

Preventing or minimizing contact between foreign travelers and your herd for the period after their arrival may also prevent the spread of other diseases as well.

Lohn, TX 76852

Phone 325-344-5775

Originator of Tennessee Meat Goats

DISEASES OF GOATS: PREVENTION, CONTROL, AND MANAGEMENT

A major concern of responsible goat producers is the introduction of diseases onto their property. Prevention is of course the producer's desire, but realistically speaking, control and management are most likely to be goal.

Disease can enter the producer's farm or ranch from many sources. Introducing new animals is the usual avenue but definitely not the only way that illness finds its way into the herd.

1) Bringing new animals into the herd from offsite. Quarantine and handling procedures will be addressed in this article.

2) Offering stud service. This typically involves bringing other producers' does onto the property for service by an on-site buck.

3) Goat shows. A huge source of infection and illness, shows are like children's day-care centers -- incubators for disease.

4) Visitors. Infectious materials can enter on visitors' shoes, clothing, and hair; on the tires of their vehicles; in hay, water, tubs/buckets, feed and other supplies that visitors have brought with them.

5) Unclean conditions in pens and pastures.

6) Poor health management practices within the herd.

7) The producer's family members and pets.

Most producers are aware that they should quarantine new animals brought from outside the ranch property in order to protect their goats from whatever diseases the new animals might be carrying. However, the reverse is just as true: newly-introduced goats need to be protected from organisms present on the ranch to which they've never had their immune systems previously exposed. Recognize that these goats are on a new property in a changed environment and often in a much different climate from which they had been previously adapted for living. From the moment they left their previous homes, these new goats' immune systems are under constant assault.

Set up a pen and shelter sized to accommodate the producer's anticipated needs and locate it away from pens and pastures where healthy animals are regularly kept. The pen should be large enough to provide space for proper exercise and should have at least a three-sided shelter with roof to protect the new goats from bad weather. Nearby but not within this pen/shelter area, there should be several smaller gated pens and sheds where sick and/or contagious animals can be confined for observation and treatment. Place a shallow plastic cat-litter pan and a gallon of bleach outside each pen and require persons entering and exiting to wet the soles of their shoes in the bleach. The producer and all other persons handling these goats should consider using disposable gloves.

New and/or ill goats should be kept in appropriate parts of these "sick pens." Goats new to the ranch should be quarantined for a minimum of four weeks, during which time they should be dewormed, vaccinated, and otherwise examined, based upon the producer's management practices. If blood testing for specific diseases is part of the program, do it while the goats are in quarantine. If the tests come back positive and the new goats are already running with the main herd, exposure to disease has probably already occurred.

Offering breeding services on the ranch is an avenue for contamination. Before making a decision to offer such services, the producer should read this writer's Article entitled Pros and Cons of Offering Breeding Services on the Articles page at www.tennesseemeatgoats.com. A lot of decisions must be made and agreements put into writing before the first goat arrives on the servicing ranch.

Participating in goat shows is almost a no-win situation with regard to disease. The producer must take extraordinary precautions to protect both goats and human participants from exposure to contagious bacteria, viruses, and other organisms. Animals and people, both young and adult, present risks to all in attendance. Consult an experienced goat-show participant to find out what steps to take to protect you and your goats from taking "unwanted visitors" home with you. At the very minimum, sick goats and ill people should not attend shows and should not be allowed to participate. If they are, leave immediately. Don't even unload your animals. The health of your goats is much more important than a forfeited entry fee or a winning ribbon.

Visitors, relatives, children, pets, and even the producer can easily bring to the ranch infectious bacteria, viruses, and other organisms without ever realizing it. Using a shallow plastic cat-litter pan and a bottle of bleach, the producer should have all visitors step through the solution. This is the very minimum protective action that goat ranchers should take. If the producer knows that visitors or family members have had direct access to goats from outside the ranch, then those folks should be asked to change clothes and shoes before they enter your property. A visit by kids to the 4H barn is a good source of contamination -- a fact that probably never crosses peoples' minds.

Unclean/unsanitary pens, feed troughs, and water containers are excellent sources of infection -- worms and coccidia oocysts thrive in these environments. Flies carry disease from goat to goat. Less often recognized is the exposure to disease that occurs when infective birthing materials are left in pens/pastures for healthy goats to contact. Infected placentas left lying around after birthing are transmitters of abortion diseases such as chlamydiosis; many other diseases are spread through placental material and mucous secretions. Footrot/footscald is highly infectious and contaminated ground very efficiently spreads these diseases. Viral-borne diseases such as some types of Pinkeye at quickly passed around in crowded herds. Caprine Arthritic Encelphalitis (CAE) is a viral disease that is spread through body fluids and mother's milk. Cutting open and draining an active Caseous Lymphadinitis (CL) abscess and exposing the exudate (pus) to other goats and the ground upon which they walk is one of the main ways that CL is spread throughout a herd. Reusing contaminated needles, syringes, and scalpels is another easy way to transmit disease.

Raising quality goats requires planning and hard work. Doing the planning part in advance will cut down on the amount of hard work each producer faces daily.

How to select a healthy goat

by Patricia Stewart

Picking a healthy goat is very important whenever you are bringing a new goat home. There are some nasty diseases with no cures, and once they get established in your soil, there's nothing you can do but start over on a new piece of land. Start out by just observing behavior and general coat condition. A healthy goat should have clear eyes and nose, a shiny hair coat with no bald patches, and a twinkle in its eye. Bald patches may be a sign of a mite or lice infection, causing the goat to rub due to irritation.

If you are buying from a breeder, ask them if they test for CAE, Caprine Arthritic Encephalitis. This disease has been an issue for a long time in goats, and thankfully, conscientious goat farmers are finally taking it seriously. There are three blood tests, any of which will give you a heads up if there's a problem. Any possibly "positive," should be automatically checked with one of the other tests to verify. CAE shows up after awhile with stiff and swollen legs, awkward walking, sometimes a click from the knees of an infected goat. The udder is often hard and the animal's coat may be oily or scaly. If you are buying from a large farm, ask if they practice CAE prevention, which means the kids are bottle fed, never nursing off of mom. CAE is most commonly spread in the milk, but often doesn't show up as an illness for many months or years.

If you see any signs of swelling beneath the jaw or any oozing sores, do not buy that goat. Do not buy a goat from that farm, and wash your hands immediately. Caseous lymphadentitis, CL, is a highly contagious disease spread by discharge. The abcesses swell up in the lymph glands and as they pop, they spread the disease.

Always ask the seller what type of vaccinations they give. When was the last time the goat was wormed, and what kind of wormer was used. A healthy goat should not have visible ribs or backbone. It should have healthy pink eyelids and gums and manure that comes in pellets, individually. A goat that is passing runny or clumpy manure is not at its best. It may just be a rich diet or stress, or it may have a severe case of worms.

Keeping a goat healthy is really pretty easy. Good hay, adequate grain, fresh water and draft free home. But curing a sick goat is often impossible. I would not recommend ever buying from a sale barn, as those animals are exposed to many different germs under high stress conditions. This makes the more susceptible to bringing a problem home with them. Often times, the animals are taken to the sale barn because they are sick, or old, and the owner can't, or doesn't want to invest in healing them.

It's a good idea to keep any new goat in isolation from the existing herd, for at least two weeks. Usually, if something is "brewing" that is enough time to see how the animal does, without endangering the rest of the herd. But remember, goats are herd animals, so if possible, buy two new ones, at least, so they can keep each other company during the quarantine. They'll be much hardier and happier that way.

Introduction to a Meat Goat Quality Assurance Program

and HACCP Roger Merkel

Langston University

Biosecurity PPP #1 - Establish a biosecurity plan for your farm

Consider your production operation and devise a plan to ensure your animals are protected from diseases entering your herd. Potential ways in which diseases could enter your farm include: visitors, feed deliveries, new animal acquisition, and show animals returning to the herd, stray animals, rodents, birds, and others. The potential risk from these various areas should be examined in the context of your production situation. Plans should be made to protect animals from identified risks and to deal with animals that become ill so that diseases occurring on your farm are not transmitted beyond your farm gate.

Biosecurity PPP #2 - Minimize or avoid contact between your animals and animals not on your farm

Many diseases are transmitted through animal to animal contact. Avoiding contact with animals not on your farm will reduce disease outbreaks. Consider the location of pastures and grazing areas in relation to your neighbors’ animals. If new facilities are planned, consider the location of neighboring livestock barns and pens. Do not build facilities in or near drainage areas from livestock facilities. If your animals are very valuable, for example breeding males whose semen is collected for sale; consider double fencing along adjoining property lines to further protect them from neighboring animals. At exhibitions, house animals using solid partitions to minimize contact. Control stray animals, both domestic and wild. Maintain quarantine procedures. Do not haul other animals with your own and clean mud and manure from livestock trailers.

Biosecurity PPP #3 - Establish a quarantine protocol for animals entering your herd

Preventing diseases entering your herd from new animals begins during purchase. Be sure to ask the seller for health and production records on animals you plan to buy. Ask about the disease or herd health program followed. Also, look at the whole herd, not just the few animals you plan to purchase. This will give an indication of the health program followed. Upon arrival at your farm, place new animals in quarantine for a minimum of 30 days. Consult a veterinarian for a quarantine vaccination and deworming protocol and any diagnostic tests that should be performed. Buckets, shovels, fencing, etc., used in the quarantine area should not be moved and used in the general herd. Feed and care for quarantined animals last and do not re-enter your herd before changing clothing and washing boots to prevent carrying diseases from new animals to your herd. As an example, if a quarantined animal has a caseous lymphadenitis abscess that bursts, a person may inadvertently step in the pus from that abscess and carry that on his or her boots. If that person then reenters the farm herd, he may contaminate the ground or other animals.

Quarantine animals upon return from exhibitions or fairs if they have had contact with other animals. Follow the same quarantine guidelines for these animals as with purchased animals. Do not haul animals other than your own to and from shows.

Biosecurity PPP #4 - Establish a protocol for visitors to your farm

Many visitors to your farm will likely be producers themselves. To ensure that diseases are kept from entering your farm area, establish a protocol for any visitors and their vehicles. Control traffic entering your farm and have a separate parking area or ensure that vehicles are clean of mud and manure. This includes livestock trailers, feed delivery trucks, and veterinary vehicles. Consider having disposable boots available for visitors who wish to tour your facilities and herd. Alternatively, have a footbath with disinfectant where visitors can clean their shoes before and after seeing your animals. Have a wash basin or facility for visitors to wash their hands before and after handling animals. Explain that your procedures protect not only your herd, but theirs as well.

Biosecurity PPP #5 - Do not allow persons who have had contact with livestock in foreign countries on your farm, or bring clothing or other items from them to your farm, for a period of 5 days after their arrival in the U.S.

Largely in response to outbreaks of Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) in other countries, the USDA published guidelines for persons from, or who have traveled to, foreign countries where FMD is present. These persons are encouraged not to have contact with livestock for 5 days after entering the U.S. Some states or institutions, such as Langston University, recommend a 10-day waiting period. The virus causing FMD can be carried in hair and nasal passages, clothing, luggage, shoes, etc. Following this PPP helps safeguard the entire U.S. livestock industry. Outbreaks of FMD, while not a threat to humans, result in the necessary destruction of all infected and potentially infected animals with enormous industry and economic consequences.

Preventing or minimizing contact between foreign travelers and your herd for the period after their arrival may also prevent the spread of other diseases as well.

18.12.09

Cashmere Processing and Harvesting Procedures

The Need to Understand Cashmere Processing and Harvesting Procedures

Mickey Nielsen, Liberty Farm Cashmere 2009

This article must be reproduced in its entirety and the name and contact information must be included at the beginning of any reprint. americancashmere@aol.com

Understanding Processing

Before you harvest your cashmere it is important to understand the mechanical processing of cashmere. Because the Cashmere goat has a dual coat (guard hair and down) it must be placed through a separator/dehairer. This separator/dehairer works by centrifugal force. As it spins around the heavier weight guard hair is thrown down to the under bins and the lighter cashmere fiber continues to travel to the end of the processer. When the guard hair is too long and fine it holds tight to the spinning drums and is not thrown down. Then the processing must stop to clean all the long guard hair from the drums as no other fiber can be processed until it is removed. This causes time loss and added cost to you the client. At times the guard hair cannot be completely removed; if it is too long or too fine then processing has to stop.

The scoured cashmere is placed through the separator a minimum of five times and it takes a minimum of six hours for each pound of cashmere.

What causes your fleece to travel through that separator more than the minimum is what you need to know about. Because the more times your fleece has to go through the separator the more potential damage happens to your delicate cashmere. You as the breeder/producer can control the quality of your cashmere product with some understanding and a few extra steps at harvest time.

The list of quality inhibitors looks like this;

too much guard hair, too long of guard hair, too fine of guard hair, matted down, short down, inconsistent length of down, weathered tips, vegetation contamination, and mixed grades.

Too much guard hair; this can be something that you need to correct in your breeding. As in some goats have high density of down and some have low density of down in relation to the guard hair. If you want to improve your yield improve your density first. The other reason you may have too much guard hair is the failure to skirt your shorn fleece before sending it into the processor. Many cashmere goats have excessive guard hair on the breech area. Taking a close look at this area before including it in your line can improving your product.

Too long of guard hair; this too can be changed with your breeding program. Any guard hair more than an inch longer than the down is too much. This can also be changed in the shearing shed by doing a double shear. Double shear means cutting off all the excessively long guard hair before you shear off the complete fleece. Skirting your fleece after you shear to eliminate the long guard hair is another option, but this is very time consuming and for most producers it just doesn’t happen. This is done by spreading the fleece out and pulling all the long guard hairs out of the shorn fleece.

Too fine of guard hair; can only be corrected through breeding. This is a really nasty problem to deal with because the dehairer cannot remove guard hair that is of the same micron as your down. You want the guard hair to be two to three times the micron of down. The dehairer also can not remove kemp (hollow cored hair).

Matted down; it is important to shear your cashmere goats before they start to shed, once they start to shed the down becomes trapped in the guard hair and if not removed quickly it becomes matted. If you cannot easily pull the mats apart with your fingers the separator cannot dehair it. Do not include these kinds of mats in your line.

Short down; is generally a breeding problem and needs to be corrected there. If you have goats with short down (less than 1.25 inch) it may be best to comb the down out as this does not cause any loss of length as shearing does. Short down will be kicked out of the separator with the guard hair.

Inconsistent length of down; is a breeding issue and a skirting issue. If you have a goat with major inconsistent lengths of down, separate out the areas of different lengths into different lines. Consistency is very important to look at when considering a goat for breeding.

Weathered Tips; is caused when guard hair does not cover the down. This must be taken into account when measuring the length of the fiber, and placing it into a processing line as these tips will become noils and may cause processing problems.

Vegetation contamination; “Being frugal and keeping 'every little bit' is not a benefit. It is like adding moldy strawberries into your fruit salad.” Diana Blair, Going to The Sun Fiber Mill.

Some parts of the fleece you just have to throw away because of the vegetation. If you don’t take it out at harvest time it will contaminate the whole clip.

Mixed grades; can ruin your end product. Educate yourself to detect fine from coarse fiber. Know what cashmere is and what cashgora is.

The first year clip is actually the hardest to dehair. The micron count between the guard hair and down is almost the same, plus the down tips are what the goat was born with and has very poor tencel strength, thus causing breakage and noiling. Some producers shear off the baby fleece in June for this reason.

Keep the baby fiber out of your other fiber

The Harvest

Plan to harvest on days that are dry and your goats are dry. A fleece that is wet or damp from snow or rain is very difficult to harvest and does not store well. Depending on where you live you may have to shut them up for a day or two to keep them dry before harvesting.

It is recommended that you shear your goats from youngest to oldest and white to dark. This helps to ensure two things. Shearing your younger goats first helps avoid accidently spreading any illness or disease that your older goats may have. White to dark fiber keeps your white line of fiber pure from dark hairs. Do not plan to trim hoofs at the same time as shearing, this can cause those trimmed hoof parts to get caught up in the shorn fleece. Processers hate this as it is hard on their equipment.

Tools and Equipment

Shearing: Cashmere goats are typically shown in the standing position.

You will need a stanchion or a head-bail to secure your goats in while shearing, quality power shears, new teeth and cutting blade for every 10 goats, shear oil, blade lubricant and blade cleaner. Individual marked bags for each fleece or grade lines, a garbage bin, broom, power outlet, and good lighting.

Combing: All the above apply except the power shears. Although a smaller grooming clipper set is nice to have on hand to tidy up the rear end. Double coated dog combs or rakes work well for combing cashmere goats. Find one with a nice comfortable grip that fits your hand well. You don’t want the rake to wide as they can be hard to work with.

Draft; your goats into handling pens noticing which goats look like their coats are lifting. These goats are the goats you want to harvest first. Draft them into pens according to age, sex, and color. Work from youngest to oldest, lightest to darkest. This is a great time to also get a good look at the condition of your goats and to give any needed boosters or parasite control.

Consider how long your goats will be penned up and if they require shade, food and water. Also notice the conditions you will be working in and what your requirements will be.

Sample the Fleece; once the goat is in the stanchion in three to five spots to compare uniformity and fineness grade. Also take note of vegetation in fleece and long guardhair. Decide what needs to be removed from the clip and if the clip needs to be sorted into different grades.

Recording the correct fleece weight harvested for each goat is important for clip improvement in the future. Record the method of harvest, uniformity, fineness, weight, color and any other trait that you desire. It is important to keep records on your harvest so you can keep improving your clip. Have each goat’s records and record all information gathered.

Skirting; the fleece can happen while you shear or after you shear. Skirting must be done while you comb as trying to remove lesser quality fiber after you comb is more difficult.

To skirt while you shear, decide which areas of the fleece you will not be keeping in the clip and toss these areas aside as you shear. You will not keep areas that have heavy vegetation (top line or neck), shorter than 1 ¼ inches, heavy stains, excessive guard hair to down ratio, matted or dung filled fiber.

If the fleece has more than one color, fineness grade or one inch difference in length from neck to breech; separate these areas into different lines.

Summary

The more understanding you can gain about the processing of animal fibers, the different pitfalls to avoid in your clip, and a better idea of what your animals produce the greater chance you have of producing quality cashmere products with less waste of your time and effort.

The need to place your fiber into as few of grade lines as possible and the need for a quality end produce have to be balanced. This is why consistency in your herd is important. You are charged for processing a minimum of one pound for each grade line.

There is much to learn about your cashmere goats and the process of producing quality cashmere products. Don’t give up, just keep learning. Ask your processer what you can do to improve your clip for next year. All of this will help to ensure a quality return product in the end.

Mickey Nielsen, Liberty Farm Cashmere 2009

This article must be reproduced in its entirety and the name and contact information must be included at the beginning of any reprint. americancashmere@aol.com

Understanding Processing

Before you harvest your cashmere it is important to understand the mechanical processing of cashmere. Because the Cashmere goat has a dual coat (guard hair and down) it must be placed through a separator/dehairer. This separator/dehairer works by centrifugal force. As it spins around the heavier weight guard hair is thrown down to the under bins and the lighter cashmere fiber continues to travel to the end of the processer. When the guard hair is too long and fine it holds tight to the spinning drums and is not thrown down. Then the processing must stop to clean all the long guard hair from the drums as no other fiber can be processed until it is removed. This causes time loss and added cost to you the client. At times the guard hair cannot be completely removed; if it is too long or too fine then processing has to stop.

The scoured cashmere is placed through the separator a minimum of five times and it takes a minimum of six hours for each pound of cashmere.

What causes your fleece to travel through that separator more than the minimum is what you need to know about. Because the more times your fleece has to go through the separator the more potential damage happens to your delicate cashmere. You as the breeder/producer can control the quality of your cashmere product with some understanding and a few extra steps at harvest time.

The list of quality inhibitors looks like this;

too much guard hair, too long of guard hair, too fine of guard hair, matted down, short down, inconsistent length of down, weathered tips, vegetation contamination, and mixed grades.

Too much guard hair; this can be something that you need to correct in your breeding. As in some goats have high density of down and some have low density of down in relation to the guard hair. If you want to improve your yield improve your density first. The other reason you may have too much guard hair is the failure to skirt your shorn fleece before sending it into the processor. Many cashmere goats have excessive guard hair on the breech area. Taking a close look at this area before including it in your line can improving your product.

Too long of guard hair; this too can be changed with your breeding program. Any guard hair more than an inch longer than the down is too much. This can also be changed in the shearing shed by doing a double shear. Double shear means cutting off all the excessively long guard hair before you shear off the complete fleece. Skirting your fleece after you shear to eliminate the long guard hair is another option, but this is very time consuming and for most producers it just doesn’t happen. This is done by spreading the fleece out and pulling all the long guard hairs out of the shorn fleece.

Too fine of guard hair; can only be corrected through breeding. This is a really nasty problem to deal with because the dehairer cannot remove guard hair that is of the same micron as your down. You want the guard hair to be two to three times the micron of down. The dehairer also can not remove kemp (hollow cored hair).

Matted down; it is important to shear your cashmere goats before they start to shed, once they start to shed the down becomes trapped in the guard hair and if not removed quickly it becomes matted. If you cannot easily pull the mats apart with your fingers the separator cannot dehair it. Do not include these kinds of mats in your line.

Short down; is generally a breeding problem and needs to be corrected there. If you have goats with short down (less than 1.25 inch) it may be best to comb the down out as this does not cause any loss of length as shearing does. Short down will be kicked out of the separator with the guard hair.

Inconsistent length of down; is a breeding issue and a skirting issue. If you have a goat with major inconsistent lengths of down, separate out the areas of different lengths into different lines. Consistency is very important to look at when considering a goat for breeding.

Weathered Tips; is caused when guard hair does not cover the down. This must be taken into account when measuring the length of the fiber, and placing it into a processing line as these tips will become noils and may cause processing problems.

Vegetation contamination; “Being frugal and keeping 'every little bit' is not a benefit. It is like adding moldy strawberries into your fruit salad.” Diana Blair, Going to The Sun Fiber Mill.

Some parts of the fleece you just have to throw away because of the vegetation. If you don’t take it out at harvest time it will contaminate the whole clip.

Mixed grades; can ruin your end product. Educate yourself to detect fine from coarse fiber. Know what cashmere is and what cashgora is.

The first year clip is actually the hardest to dehair. The micron count between the guard hair and down is almost the same, plus the down tips are what the goat was born with and has very poor tencel strength, thus causing breakage and noiling. Some producers shear off the baby fleece in June for this reason.

Keep the baby fiber out of your other fiber

The Harvest

Plan to harvest on days that are dry and your goats are dry. A fleece that is wet or damp from snow or rain is very difficult to harvest and does not store well. Depending on where you live you may have to shut them up for a day or two to keep them dry before harvesting.

It is recommended that you shear your goats from youngest to oldest and white to dark. This helps to ensure two things. Shearing your younger goats first helps avoid accidently spreading any illness or disease that your older goats may have. White to dark fiber keeps your white line of fiber pure from dark hairs. Do not plan to trim hoofs at the same time as shearing, this can cause those trimmed hoof parts to get caught up in the shorn fleece. Processers hate this as it is hard on their equipment.

Tools and Equipment

Shearing: Cashmere goats are typically shown in the standing position.

You will need a stanchion or a head-bail to secure your goats in while shearing, quality power shears, new teeth and cutting blade for every 10 goats, shear oil, blade lubricant and blade cleaner. Individual marked bags for each fleece or grade lines, a garbage bin, broom, power outlet, and good lighting.

Combing: All the above apply except the power shears. Although a smaller grooming clipper set is nice to have on hand to tidy up the rear end. Double coated dog combs or rakes work well for combing cashmere goats. Find one with a nice comfortable grip that fits your hand well. You don’t want the rake to wide as they can be hard to work with.